By Curt Burnette

In the 1989 movie, Field of Dreams, farmer Ray Kinsella hears a voice whisper to him as he walks through his cornfield in Iowa. The voice tells him, “If you build it, he will come.” In this fantasy movie, Ray builds a baseball diamond in his cornfield and long dead baseball players such as Shoeless Joe Jackson magically appear to play. Ray’s long estranged father also shows up as the young catcher behind home plate, and he and Ray make some amends. At one point, Ray s told that people will come to his field, they will be drawn there. And, at the end of the movie, hundreds of people are seen driving down the road to the “field of dreams: to watch the “big show”, as major league baseball is called.

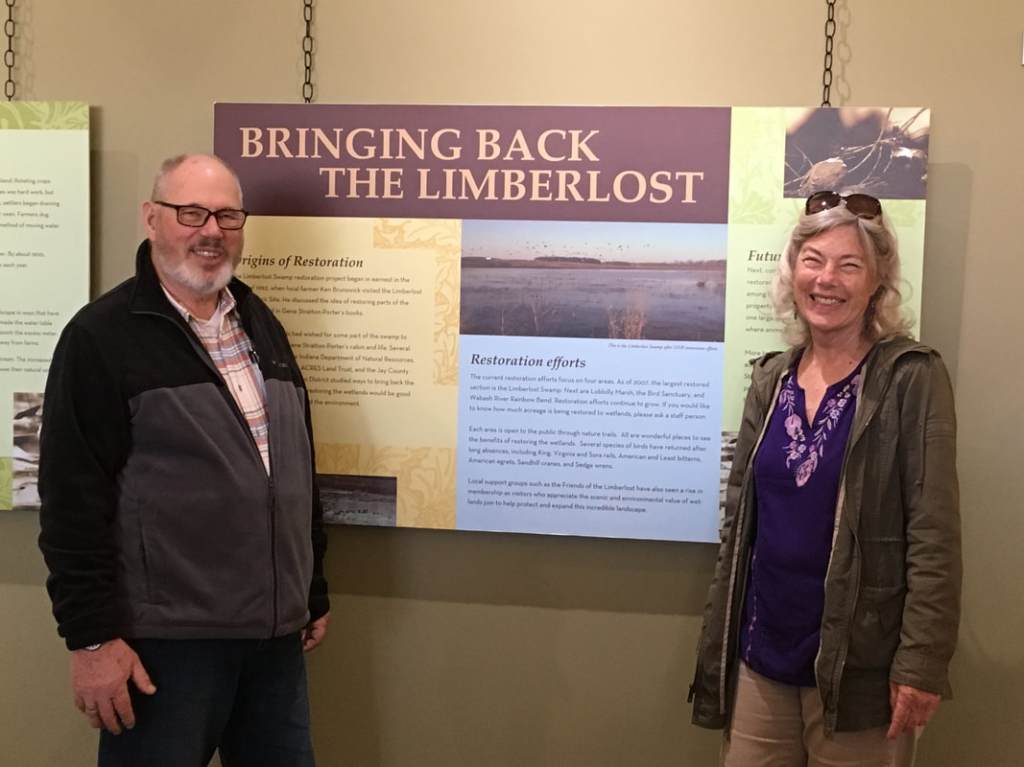

I don’t think Ken Brunswick heard any voices when he began his quest of restoring portions of the Limberlost. (Did you Ken?) nevertheless, the theme of the movie is relevant to what is happening with the restoration of the Limberlost. Instead of saying “If you build it, he will come”, it could be said of the Limberlost, “If you restore it, they will come.”

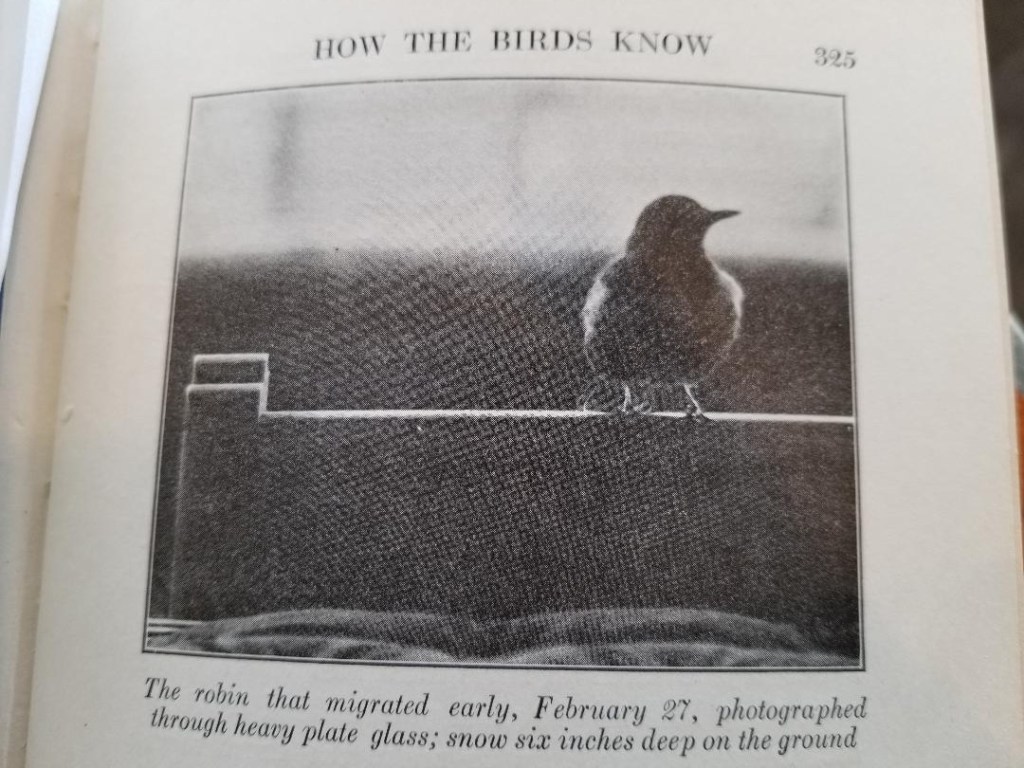

“They” in this instance would be birds of all sorts and types. The marshes, forests, and prairie-like areas of the Limberlost provide wonderful habitat for all kinds of migrating and nesting birds. Species of birds whose numbers had dwindled in this area are reappearing. Even one species never seen here before, the black-necked stilt, has recently been sighted. Migratory waterfowl such as tundra swans and pintail duck stop over on their journeys and sometimes spend the winter, if it is mild enough. Winter visitors from the north such as northern harrier hawks and short-eared owls find refuge here. Both of these species are listed as endangered in Indiana. And many, many birds such as eastern kingbirds, indigo buntings, spotted sandpipers, and dickcissel nest in the Limberlost.

Birds are like the baseball players in the movie who came to take advantage of the ball field after Ray created it. But baseball fans also came to the field to watch the players. Our comparison of the Limberlost to the field of dreams still holds true there. As more and more birds come to the Limberlost to the Limberlost to “play”, more and more bird “fans” will come to watch. Birdwatchers, known nowadays as “birders”, will travel far and wide to areas where birds are plentiful. Much like baseball fans who buy hot dogs and peanuts while watching the game, birders buy gasoline and lunch and souvenirs when they come to a birding site. Dollars spent by outsiders is good for our communities. Like building a ballpark in a cornfield, Ken Brunswick’s field of dreams has returned over 1600 acres [currently about 1800 acres] of opportunity to the Land of the Limberlost. Hundreds of people are already driving down the roads to watch the “show.”

Source: First published in the Limberlost Notebook column in the Berne Witness in June 2013.

Blue-winged teal by Bill Hubbard

Dickcissel by Kimberley Roll

Black-necked stilt

Pintails along with some mallards

Sandpiper