By Kevin Kilbane with the News-Sentinel

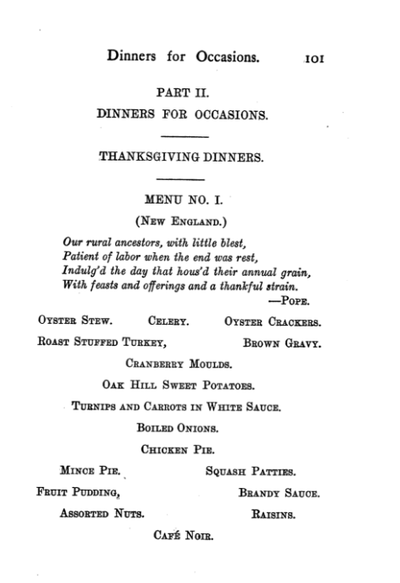

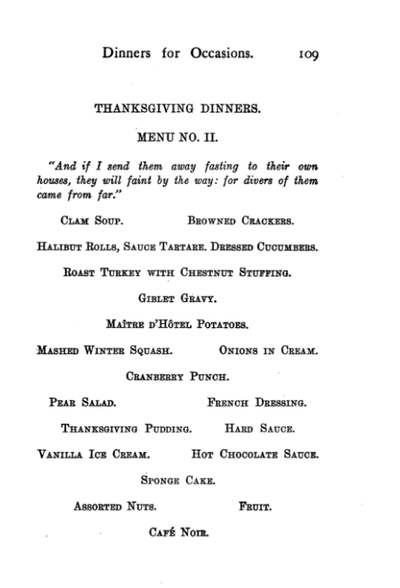

Her wedding announcements were simple and calling card size, inviting people to her marriage at 9 p.m. April 21, 1886, to Charles Porter of Geneva. The bills show it was a frugal affair.

Those are just two items in a new collection of letters, documents and photos that offer brief glimpses into the life of famed Indiana author and naturalist Gene Stratton-Porter and her family.

The collection, which the Indiana Historical Society (IHS) acquired this summer, recently became available for viewing in the IHS library in Indianapolis. Staff there also have begun making digital scans of items in the collection so they can be viewed online.

The collection contains no startling revelations, said Terri Gorney of Fort Wayne, who has been researching the author’s life and connections to Fort Wayne.

Gorney had hoped to find clues about whether Stratton-Porter owned a home in the 2400 block of Forest Park Boulevard in Fort Wayne. Property records for the house suggest she bought the lot and built a home there.

The IHS collection, which includes some items from 1886 and then jumps to the period of 1916-1923, doesn’t contain any references to a Forest Park Boulevard house, said Gorney, who drove to Indianapolis recently to see the collection with Randy Lehman, the recently retired site manager of one of Stratton-Porter’s former homes, the Limberlost State Historic Site in Geneva.

A RARE FIND

Lehman described the IHS collection as “a big deal.” Possibly because Stratton-Porter died unexpectedly at age 61 in a December 1924 car crash in Los Angeles, there doesn’t seem to have been an effort to create a formal archive of her letters, photos and other records, he said. Items such as those in the IHS collection are scarce.

“Anyone wanting to know Gene better can read through many letters, almost all of them typed, and look at many photographs for insight and historical reference,” Lehman said in an email.

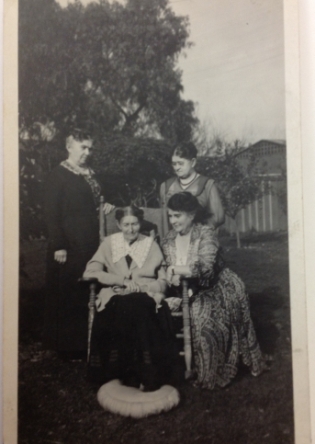

Two photos really captured his attention:

* One is a “very rare” image showing Charles Porter with Gene, their daughter Jeannette’s two daughters, and other family members.

* The other shows the two granddaughters sitting on steps with a cousin, Leah Stratton.

“This picture was taken at the Limberlost Cabin in Geneva, and it clearly shows them sitting on steps that led up to the ice box just off the kitchen porch,” Lehman said. “We always thought the steps would have been necessary for the iceman to deliver ice to GSP’s (Gene Stratton-Porter’s) icebox, but it was just a theory — the original steps, if they were ever there, are long gone.

“Now we have a photograph that clearly shows the steps with GSP’s grandchildren sitting on them,” Lehman said. “It’s also proof that GSP and the grandchildren visited Geneva after she had moved into her Rome City home, which is the opposite to what some people claim — that GSP never came back to Geneva once she left in 1913.”

INTERESTING DETAILS

Gorney found interesting and sometimes humorous details in letters in the collection:

The documents include a typed version of Charles Porter’s first letter to Gene, who was born Aug. 17, 1863, near Wabash. Porter describes seeing her at a Chautauqua event in Rome City and on the train departing there afterward. With the clumsiness and salesmanship of a man clearly smitten, he invites her to begin corresponding with him.

In a May 28, 1886, letter to her father about a month after her marriage, Stratton-Porter mentions buying paints, brushes and art canvas at Keil Bros. in Fort Wayne, Gorney said. Some of the first paintings she did as a newlywed likely were with paints purchased in Fort Wayne.

In a Feb. 10, 1919, letter to her sister Ada Wilson of Fort Wayne, Stratton-Porter asks her sister to go get a certificate of deposit Stratton-Porter had at the local Tri-State Loan & Trust. But she asks Wilson not to mention it to Charles Porter or their daughter, Jeannette, because they didn’t know she had it.

Stratton-Porter grew up in a financially insecure household, so that may be why she kept some money of her own, Gorney said.

In another letter, Stratton-Porter tells her sisters that, in case she dies, she has set aside $5,000 in savings for Leah Stratton. Gene became Leah’s guardian after the 1916 death of Lemon Stratton, Gene’s brother and Leah’s father.

In a Sept. 7, 1919, letter to Wilson, Stratton-Porter mentions sales of her books declined dramatically during World War I. “I had to use a microscope on the check,” she said, referring to her payment.

However, in a March 6, 1923, letter to sister Florence Compton of Fort Wayne, Stratton-Porter proudly shares that she was paid $12,500 for her poem “Euphorbia,” the most she had ever received for her poetry, Gorney said.

EXCITING TIMES

Stratton-Porter had moved to the Los Angeles area in 1922 to get involved in filmmaking, and letters to her sisters describe the exciting lifestyle there.

“I met a string as long as your arm of etchers, painters, sculptors, with a sprinkling of poets and authors, and I had such a glorious good time that I wish I could do that kind of a party over twice each week all the rest of my life,” Stratton-Porter said in one letter.

Letters in the collection also show she didn’t forget her rural Indiana roots, Gorney said. Even after becoming a popular author, Stratton-Porter wrote to her sisters about things such as cleaning house, canning food and trying to find cheap peaches to make peach butter and peach jelly.

“She was a regular person,” Gorney said.

Gorney and Lehman both believe more of Stratton-Porter’s letters and papers still exist in private hands.

Now that IHS has started a Gene Stratton-Porter collection, Gorney hopes people will donate items to it so we all can learn even more about the author’s life.