An Indiana Woman’s Novel

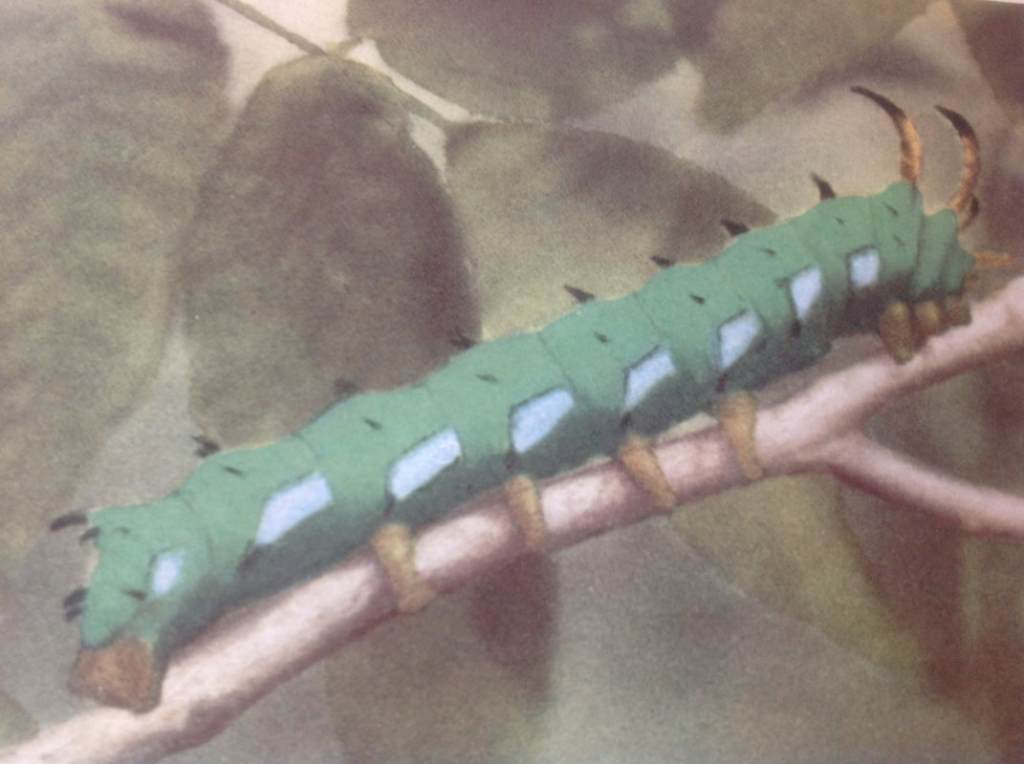

About a year ago “The Song of the Cardinal” a book written by Mrs. Gene Stratton-Porter, an Indiana woman, attracted attention because of the new note it struck in the nature study line. “Freckles,” her latest production, just issued by Doubleday, Page & Co., is a more ambitious effort. It, too, deals with out of door life—the forest, the birds and the flowers—but, in addition it contains a love story of an ardent sort. The scene is laid in and about the Limberlost, the big tract of forest land mentioned in “The Song of the Cardinal,” and supposed to be located in northern Indiana. The hero, a nameless youth known as “Freckles” is in the employ of a lumber company and in his work as watchman of the timber tract acquires a deep love for the wild things of the wood. His sympathy for and acquaintance with birds are especially great and he finds welcome companionship among the feathered creatures. A “woman with a camera,” who also loves birds, comes to know him and through her he meets “Angel,” a young girl of marvelous attractiveness with whom he falls hopelessly in love. There are difficulties and complications, because he is a nameless waif, but these are eventually cleared away. There are also adventures, dangers, and even tragic occurrences, but they only serve to throw the final happiness into relief.

The enthusiasm for nature which pervades the tale is given an intensity to which the average reader will hardly be able to rise, but as it is in keeping with the tone of the nature literature now so popular, perhaps no criticism belongs to it on that account.

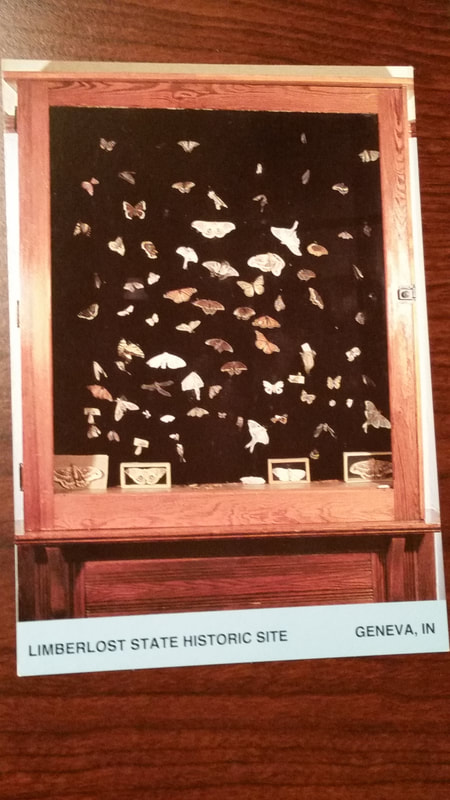

The book is likely to be widely read. The volume is profusely illustrated by Earl Stetson Crawford.

A Decatur, Ind., correspondent has this to say of the author and her work “Gene Stratton-Porter is an Indiana woman, a native of Wabash, where she has a host of friends. She has worked all her life to fit herself for a literary career and began publishing four years ago. She is an ardent lover of nature and in order satisfactorily to illustrate her writings in this line she has so mastered the camera that her right to the position of the greatest living photographer of birds is undisputed. No one approaches her work in bird pictures. For the past four years the editors of the Photographic Times Annual Almanac have tendered her first place in natural history photography.

“She was for two years the nature historian of the staff of Outing, and it as on that publication that her skill with the camera became evident and the charm of her nature writings was recognized. All of her short stories she has sent to the Metropolitan, whose editor accepted her first venture in that line and immediately invited her to write his leader for the following Christmas.”

“As she only does nature illustration Mr. Crawford was sent to her home to draw the characters for her novel under her supervision, so that they could not fail to illustrate and harmonize with the story.”

“Mrs. Stratton-Porter lives in a picturesque log cabin, designed by herself, at Geneva, Ind. She devotes all her time to her camera work afield and to literary work at home.”

Source: The Indianapolis Star, 6 Nov 1904, p. 13.

Notes:

The Limberlost was once 13,000 acres in southern Adams and northern Jay Counties. Today the Friends of the Limberlost and DNR Nature Preserves is working to restore some of these wetlands that Gene Stratton-Porter made famous.

The inspiration for her book was Ray Boze who worked for Gene.

E. Stetson Crawford spent part of the summer of 1904 in Geneva illustrating “Freckles.”